After a season of indulgence, many Americans resolve to drink less in the new year. It’s a common pledge — many of us can recall cringe-worthy texts sent after a raucous night out or a regrettable comment uttered after that third glass of wine.

These intentions are rooted in a stark reality. For all the deserved attention the opioid crisis gets, alcohol overuse remains a persistent public health problem and is responsible for more deaths, as many as 88,000 per year. While light drinking has been shown to be helpful for overall health, since the beginning of this century there has been about a 50 percent uptick in emergency room visits related to heavy drinking. After declining for three decades, deaths from cirrhosis, often linked to alcohol consumption, have been on the rise since 2006.

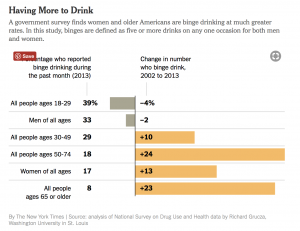

The pattern has been years in the making. Rick Grucza, an epidemiologist who has been studying alcohol consumption patterns for more than a decade, says the numbers are incontrovertible. Since the early 2000s, according to five government surveys Dr. Grucza has analyzed, binge drinking — often defined as five per day for men and four per day for women — is on the rise among women, older Americans and minorities.

Behind those figures there’s the personal toll — measured in relationships strained or broken, career goals not met and the many nights that college students can’t remember. In researching my 2013 book on women and drinking, and many articles on the topic since, I’ve spoken with hundreds of problem drinkers of all races. Most of the people I’ve spoken to were college-educated; it’s a sad fact that many people learn to drink excessively in college. I found that a lot of people lack physical symptoms of alcohol dependence but they think they are overdoing it, and they are worried.

The superrich might be making money, Dr. Tatarsky said, but many others are just worried about making ends meet. Uncertainty about tax changes and the cost of health insurance only adds to their burden.

And the culture around drinking, the way we drink, has grown more intense. Epidemiologists say that excessive and binge drinking begins in college, and that for many it continues through early adulthood with after-work happy hours — so much so that Thursdays, in many circles, have become “Little Friday”— code for hitting the bar after (or in some Silicon Valley companies during) work.

Cues from popular culture make alcohol look glamorous and fun: “They send the message that you’re missing out if you are not up on the latest cocktail,” said Carrie Wilkens, also a clinical psychologist treating substance abuse. And as adults age and feel burdened by the responsibilities of family and work, drinking can be an instant stress reliever.

Many who struggle with drinking aren’t getting the help they need, largely because they think that the only way to gain control over alcohol is to abstain. Facing such a severe restriction, they may not try to change unless they hit a mythological “rock bottom.”

Nobody wants to view himself as an addict, and the fact of the matter is most problem drinkers aren’t. Many people are afraid even to discuss the topic with their doctors for fear of being labeled. But in fact, researchers have long shied away from using the term “alcoholic,” because it’s both negative and dated.

In the DSM-V, the new term to describe problematic drinking is alcohol-use disorder — a clunky but more expansive phrase that denotes a spectrum of risky drinking from mild to moderate to severe. Only about 10 percent of the estimated 16 million Americans who abuse alcohol fall into the severe category, according to Reid Hester, a clinical psychologist who has been studying addiction for more than 40 years. While those in the severe category might need to abstain from drinking, the vast majority of others don’t, he said.

Newer treatments embrace an array of techniques and are effective for those with mild and moderate problems. A great deal of research supports the use of anti-craving medications, such as naltrexone, and harm-reduction therapy, which Sheila Vakharia, an assistant professor of social work at Long Island University, says provides practical tools for solving behavioral problems.

Many of the new treatments help people track their drinking — and perhaps most important, understand why they’re imbibing in the first place. Dr. Tatarsky, for instance, teaches patients to learn how to “surf” their urges — taking 15 seconds to notice the emotion that might be causing them, and then substituting healthier behaviors such as breathing exercises. He also teaches strategies: “Before you go to a party, before you set out on your week, it’s useful to have a plan, just like athletes have game plans.”

Others offer web-based methods to curtail drinking, and in some initial research, they have shown promise.

Dr. Hester founded Checkup and Choices, a company that sells a web-based tool for reducing drinking. Since 2003, more than 60 percent of the 22,000 users of the app have been women.

Drinking poses special risks for women, of course. They’re almost twice as likely as men to have anxiety disorders, which they often medicate with alcohol. And biologically, women are more at risk for alcohol’s intoxicating effects.

Because of the stigma associated with alcohol problems, women — especially those with children — are less likely to seek help. Dr. Hester believes that since web-based programs are confidential and available around the clock, women are more likely to turn to them.

The news about our alcohol habits may seem grim, but there’s room for hope. I’ve been inspired by stories of the people I’ve met who’ve overcome drinking problems. One of my favorites is Jane, a Virginia businesswoman who found her drinking spiraling out of control after her company went under in 2009. She used a harm-reduction suggestion of abstaining for 30 days — at first a challenge — and then reintroduced alcohol while chronicling her thoughts, feelings and cognitive abilities after each drink on note cards.

She recognized a stark pattern: She felt happy and lucid after her first and second drinks, but sloppy and maudlin after her third and fourth. She taped the note cards on her refrigerator and kept them up for a year as a reminder of how bad she felt after that third drink. Years on, she still thinks about those notes, especially during these stressful times. More often than not, she switches to water.

“Happiness,” she said, “doesn’t come in a bottle.”