When Barb Clark and her husband Michael adopted their oldest daughter Akila at 5 months old they never envisioned the difficult road ahead. What the Minneapolis, Minnesota-based Clarks couldn’t see when they rocked, fed and loved their infant daughter was the brain damage that she already had because of prenatal exposure to alcohol.

“As soon as she was walking and talking I knew things were a little off,” Barb said. “Consequences never worked for her, and she was 2 years old when she stole for the first time.”

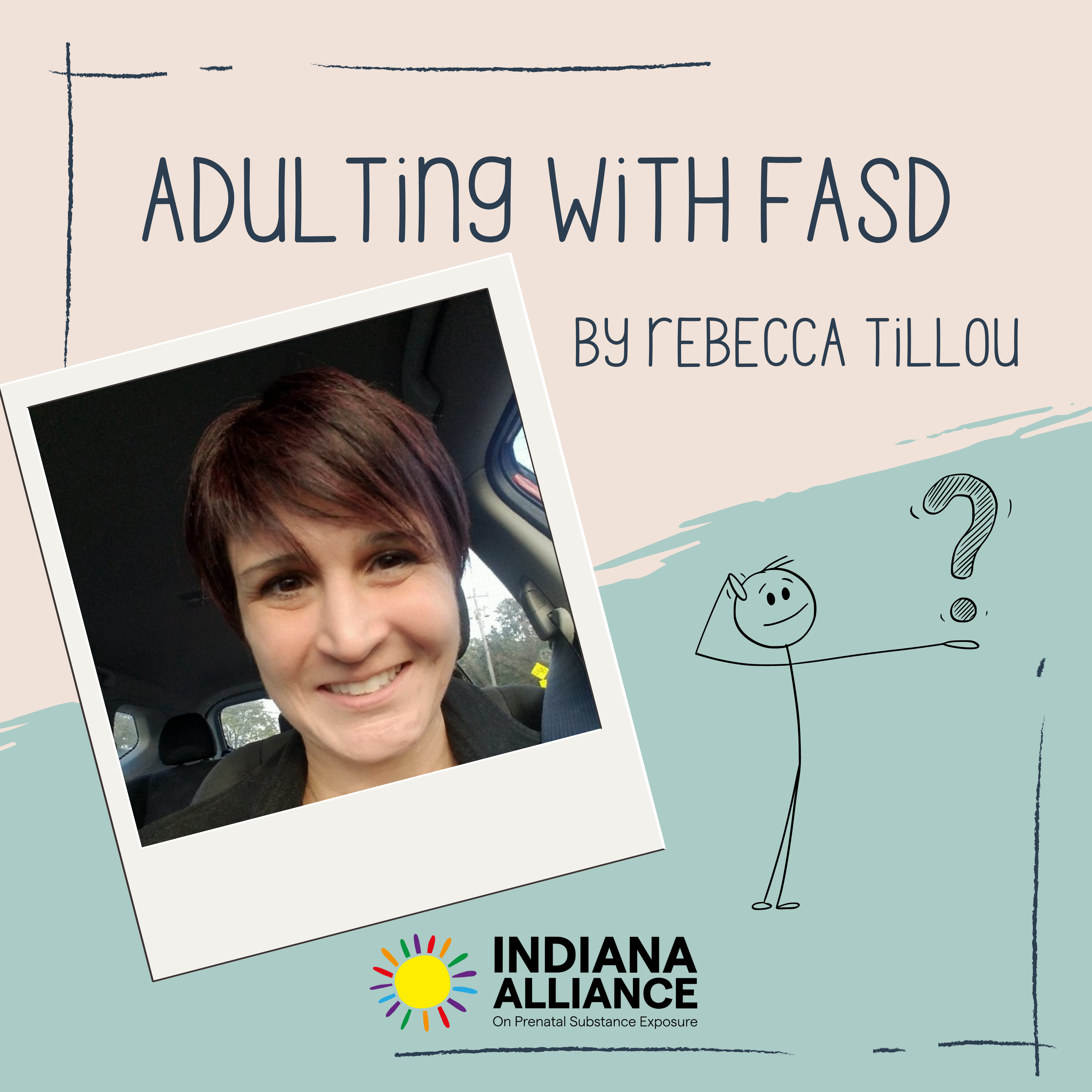

Michael and Barb Clark with their four children they’ve adopted. Their daughter Akila lives with a Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD).

While “stealing” is a typical behavior for toddlers who don’t yet understand the concept, Akila’s early tendency to take things and to not learn from any consequences was concerning to the new parents. Other behaviors such as her high energy, attention-seeking and sleeplessness caused the couple to seek out guidance from medical professionals, but their concerns were often dismissed.

Finally, Barb began researching some of the behaviors online and found sites about Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). With research in hand, the Clarks sought out a new pediatrician who was more willing to listen to their concerns about their daughter. Finally, at age 6, Akila was diagnosed with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome.

Akila is one of the thousands of children in this country living with FASD, which is the umbrella term for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS), Alcohol-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder (ARND) and Alcohol-Related Birth Defects (ARBD). While it’s unknown how many people in America have one of the disorders, the CDC estimates that up to 1.5 infants are born with FAS for every 1,000 live births.

Other studies of school-age children estimate 6 to 9 our of 1,000 children have FAS, which puts the occurrence at about half the frequency of autism. But a new study of 6,639 first-grade children by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism have bumped estimates to 11.3 to 50 per 1,000 children. According to the CDC, the lifetime [societal] cost for one individual with FAS in 2002 was estimated to be $2 million.

For the Clarks, parenting Akila has continued to be a challenge. They’ve had to learn along the way how to look at their daughter’s behavioral issues differently, recognizing that brain damage causes those behaviors. Over the years, they’ve had to adjust their parenting styles and how they respond to their daughter and her behavior. Even though Akila was 6 when she was diagnosed, it wasn’t easy to shift parenting techniques.

“It still took us several more years to wrap our brains around it,” Barb said. “We’re dealing with children with a brain injury that plays out very behaviorally.”

Now, Barb helps others understand the impacts of FASDs. As parent support coordinator for the North American Council on Adoptable Children (NACAC), Barb trains parents and professionals on a number of topics, including parenting children with FASDs. Much of that training is offered at foster care agencies and to foster parent groups.

“It’s been estimated that 80 percent of children in foster care have an FASD,” Barb said. “I don’t think in the foster and adoptive community we’re talking about fetal alcohol enough.”

Dr. Doug Waite agrees. As medical director at the Keith Haring Clinic at New York’s Children’s Village, he’s worked with many children with FASDs in the past 16 years. But prior to that, Waite said it wasn’t really on his radar screen and was barely touched on during medical school and residency training.

“Working here, I started seeing a lot of kids in our residential treatment center (RTC) that nobody could really take care of because of behaviors,” Waite said. “No one knows for sure [how many have FASDs] because kids aren’t being diagnosed. You can’t get a clear history of alcohol use [prenatally].”

Waite said it’s been hard to move the dial since 1973, when the syndrome was first named in a study published in The Lancet by Kenneth Jones and David Smith. In 1996, the Institute of Medicine published the first diagnostic categories for the syndrome.

While more research since then has confirmed the long-term effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the brain, just a few years ago a new diagnosis of unspecified neurobehavior disorder was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) that allowed practitioners to find a diagnosis fit for kids with FASDs. But Waite said few doctors and professionals are really talking about FASDs and the neurodevelopmental disorders related to it.

“After 45 years, children and adults are still not being diagnosed with FASD,” Waite said in a email. “One of the primary reasons for lack of diagnosis is the stigma associated with the words ‘fetal alcohol,’ which holds implicit judgement of the mother (‘How could she have drank alcohol during her pregnancy?’) and also the child (‘he has brain damage because his mother drank’). While both of these are true, they lack a greater understanding of how devastating the disease of substance use disorder is.”

That stigma, coupled with the fact that some of the earliest research done on FASD was done in the Native American community, mean there are layers of challenges that prevent professionals and society as a whole from taking a bigger look at the impacts of alcohol on a developing fetus, Waite said.

“It’s fraught with stigma in New York City and it’s fraught with racial overtones,” Waite said of prenatal alcohol exposure. “While we now know the women who drink most during pregnancy are white, college educated women, there continues to be an assumption that minority children are most likely to be affected, which is false.”

Kathy Mitchell has been working on FAS issues for many years as director of the National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (NOFAS), which was founded in 1990. For Mitchell, the cause is personal; her 44-year-old daughter Carly has Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Little was known about alcohol’s impacts on a fetus at the time when Mitchell, a former alcoholic, was pregnant with Carly. Mitchell is also quick to admit she drank during each of her four pregnancies, but her other children, who are now adults, don’t seem to have been impacted.

“Getting that news changed the trajectory of my entire life,” Mitchell said. “I drank before FAS was ever identified. The tragedy for me was I wish I had known not to use alcohol when I was pregnant. I felt it was my duty to inform other parents.”

Mitchell said the organization has been instrumental in getting FASDs on the radar of legislators and raising funding for research. Mitchell said the organization is constantly battling the myth that small amounts of alcohol are safe to drink during pregnancy.

“There really hasn’t ever been a scientific paper that states it’s safe to drink during pregnancy,” Mitchell said. “People in our country and around the world like to drink. It seems like a big deal to ask people not to drink for an extended period of time.”

NOFAS is working to partner with affiliates to push education. In 2016, Minnesota became the first state to require foster parents to receive training on FASDs. While the law only requires one hour of training for foster parents per year, it’s more than any other state requires.

“When we educate folks in child welfare, they get it,” Mitchell said. “Most of these folks get into it because they want to help families. Every time I do a training, it creates change agents.”

Kids with FASDs are known to be hyperactive and impulsive. Many are diagnosed with ADHD at young ages because of their inability to pay attention coupled with their hyperactivity. By upper elementary age, Keith Haring Clinic’s medical director Waite said they’re often labeled oppositional defiant and bipolar.

“We’re basically banging their heads against the desk from kindergarten through to the end,” Waite said.

While development of treatment strategies lags, there is recent hope for medicine to combat the effects of FASD. Last year researchers at Northwestern University found that some drugs help to reduce learning and memory problems and help rebuild neuropathways.

In the meantime, early intervention is the only thing that has shown signs of improving a child’s development. For families like the Clarks, that has meant shifting their expectations for their daughter and always remembering that her behaviors come from brain damage that occurred before she was ever born.

“We need to stop trying to fix them and focus on the relationship,” Barb said. “Shift how you’re doing things and you’ll see more calm in your home. There’s a lot of hope still, we just have to shift our paradigm in how we look at success.”

Today Akila is 18 years old and lives in a group home close to her family, whom she sees a couple times a week. She’s also currently enrolled in a transitional school program for youth ages 18 to 21, which focuses on vocational and life skills.

“She is an amazing and resilient young woman whom we are incredibly proud of,” Barb said. “She has overcome more obstacles in her short life than most of us can fathom.”

Credit / Sources

This article was written by Kim Phagan-Hansel, and was published online at The Chronicle of Social Change and in print in Fostering Families Today magazine.